Best Hip Bursitis Treatment Toronto | Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome (GTPS)

Hip Bursitis or GTPS is a common condition seen and managed at our Yorkville Corrective Chiropractor Toronto clinic. We consider ourselves to be amongst the best hip bursitis treatment in Toronto because we know that it is rarely actual bursitis. It is easy to diagnose and correct when you see the right practitioner.

Is the second most encountered hip problem next to hip osteoarthritis and is a general term for a syndrome where pain is experienced on the outside (lateral) thigh and is often confused for bursitis. For it being so common, it is shocking to see how many patients are misdiagnosed and the underlying problem is rarely addressed. Pain on the side of the hip is almost never a bursa in my experience but most often muscular or neurological.

If you are looking for the best hip bursitis treatment Toronto then please read on about how to best manage it.

Why is it called GTPS and not hip bursitis? | Best Hip Bursitis Treatment

Advanced imaging studies including ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have revealed that the bursal is rarely involved (more below) and that a number of anatomical structures are involved in producing the pain. It more accurately labels the syndrome and makes treatment and diagnosis more precise.

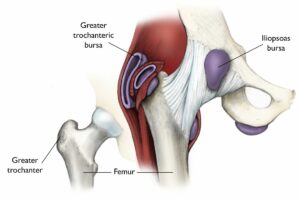

A bursa is a fluid-filled sac (think a thin, slimy balloon) that provides cushioning and lubrication between different muscles and tissues within the body

There are many bursae around the lateral hip and there exists a great deal of anatomical variation in terms of how many bursae there may be, their precise anatomical location and their pattern of pain referral. The largest and most incriminated in GTPS is the subgluteus Maximus bursa.

It is now believed that bursitis is not the chief pathophysiological cause of this condition – there is rarely any heat, inflammation, redness or swelling at the site of the site – common symptoms of true bursitis. If you want the best hip bursitis treatment Toronto then you actually can’t treat it like an inflammatory condition like bursitis. It needs to be treated like a neurological condition like back pain!

Hip Bursiti / GTPS is usually a tendon problem

There is a high association found between gluteus medius and minimus tendinopathy (degeneration of the tendon) and atrophy of the gluteus minimus with lateral hip pain occurring almost exclusively on the side of the symptomatic hip. In other words, it is likely a musculotendonous problem.

Tendon degeneration, tendinopathy, tears from overuse or trauma or inflammation of the hip abductor tendons (gluteus medius and minimus) may be another potent pain generator in GTPS.

One study found that in the majority of cases of GTPS, there was

- Tendinopathy of the gluteus medium and/or gluteus minor was the only abnormal ultrasound (US) finding in 51.61% of cases

- bursitis was the only US abnormal finding in 6.45% of examinations

- 12.9% showed a combination of both tendinopathy of the gluteus medium and/or gluteus minor and trochanteric bursitis

- The total frequency of gluteus tendinopathy was 64.51%

- No abnormal findings were found in 29% US examinations.

It is possible that in some cases, tendon pathology might actually proceed bursal inflammation and irritation or be the direct cause of it.

Best hip Bursitis Treatment Toronto: Rehab implications in GTPS

The common finding of associated gluteal muscle tendinopathy and weakness means that the condition should be treated much differently from true bursitis: retraining and strengthening of the hip musculature will be a priority

Tendons heal and respond best to loading through eccentric and sometimes concentric exercises. Because this condition is unlikely a bursa issue, which would be best with rest, the tendons should be forced to work and experience the necessary load to stimulate healing and regeneration. As with Achilles and elbow tendinopathies, a rehab program that includes stretching and strengthening is vital to heal the tendons and reduce the frequency of reoccurrence.

Proper Diagnoses Rules Other Scary Conditions Out

As in most cases, one of the most important things to do is to determine what is the actual cause of your pain and who is best to manage your condition. In certain cases, especially with acute trauma, fracture of the femoral neck (elderly mainly) or avascular necrosis (bone death from a lack of blood supply following trauma etc) can be potential causes.

Osteoarthritis, meralgia paresthetica, lumbar spine conditions, crystal deposition disorders, ITB syndrome / snapping hip syndrome, hip extensor/rotation muscle strain and infections are also potential causes of GTPS that should be ruled out by a qualified doctor, chiropractor or trusted physiotherapist.

The true cause of the condition is tough to elucidate with manual examination and advanced imaging is rarely required

Symptoms and Signs of GTPS | Best Hip Bursitis Treatment Toronto

It affects between 10-25% of the population and has been recorded at rates of 20-35% in mechanical low back pain sufferers.

Symptoms

- Chronic or acute intermittent pain or tenderness over the lateral aspect of the hip

- Up to 50% of patients may experience a sharp radiating pain along the lateral thigh up to, or past the knee.

Signs

- Lateral hip pain when side-lying on the hip

- point tenderness upon direct palpation of the lateral or posterior greater trochanter (positive jump sign)

- Lateral hip pain with resisted external rotation or resisted internal rotation

- Pain is rarely provoked by flexion or extension of the hip

- Orthopaedic testing does not appear to have the ability to differentiate between gluteus medius/gluteus minimus pathology versus bursae inflammation.

Aggravating factors to be away of include prolonged single-leg stance, lying on the affected hip, standing or transitioning to a standing position, sitting with the affected leg crossed and with climbing stairs, running or other high-impact activities

Risk Factors for GTPS

- age (40-60 years old)

- female gender (fames 4:1 to males)

- ipsilateral iliotibial band pain

- knee osteoarthritis

- obesity

- low back pain

Mechanism behind GTPS

It is possible for repetitive microtrauma causing friction or overt acute trauma to the hip such as a fall to cause irritation of the trochanteric bursae and resulting pain. However studies have demonstrated that the bursae are rarely indicated as a pain generator, never mind the only one. One study implicates the trochanteric bursae in only 8% of cases of 24 cases of GPTS imaged by MRI.

Treatment of GTPS / Best Hip Bursitis Treatment Toronto

“Most cases of GTPS are self-limiting and tend to resolve with conservative measures, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, ice, weight loss, physical therapy, and [behaviour] modification that aim to improve flexibility, muscle strengthening and joint mechanics while decreasing pain.” (Williams and Cohen, 2009)

In general, it appears that conservative care including physical rehab and manual therapy techniques has better long-term outcomes than corticosteroid injections.

- a 2009study by Rompe et al, investigated the effects of 3 treatment (corticosteroid, exercise therapy and shockwave therapy) programsforrefractoryunilateralGTPS on 229 patients

- the exercise program (2x / day, 7 days / week for 12 weeks) consisted of specific hip abductor / rotator stretches and exercises

- Stretches included: piriformis, ITB – Strengthening included: isometric gluteal strengthening, wall squats and straight leg raise

- Subjects were re-evaluated at 1,4 and 15 months to assess the degree of recovery and pain resolution

- in the short-term, corticosteroid injection was heavily favoured with 75% having significant reduction in symptoms

- However, long-term follow-up at 4 and 15 months heavily favoured shockwave and exercise interventions

- At 15 months, 80% and 74% of exercise and shockwave patients reported significant reductions in symptoms versus only 48% receiving corticosteroid injections

- The authors added that the “role of corticosteroid injection for greater trochanteric pain needs to be reconsidered

It is important to note that this study did not include the combined use of manual therapy with exercise prescription (the standard practice of most chiropractors and physiotherapists), which would surely speed the recovery process

Other studies have mirrored the findings on corticosteroid and anesthetic injections in terms of their failed long-term success. Other studies have shown that here is no major difference in using imaging-guided injections versus landmark (eyeballing it) injections

Surgical intervention and consult should only be consulted after failed conservative therapy options owing to the seriousness of potential side-effects including serious infection.

My Treatment and Rehab Focus for GTPS / Hip Bursitis

Pain management: using soft tissue massage (ART), acupuncture, or other techniques to reduce your pain quickly

Gait/biomechanics corrections: restore normal gait and movement patterns to reduce micro-trauma to the hip and prevent future recurrences

Restoring Muscle Function and Strength (Rehab): Make the hip stronger to help repair the damaged glut tendons and promote healing

Restoring Nervous System Function (Rehab and Acupuncture): Ensure that a healthy and strong nervous system is providing proper control of the glue muscles

References

Woodley, Stephanie J., Helen D. Nicholson, Vicki Livingstone, Terence C. Doyle, Grant R. Meikle, Janet E. Macintosh, and Susan R. Mercer. “Lateral hip pain: findings from magnetic resonance imaging and clinical examination.” The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy 38, no. 6 (2008): 313-328

Rompe, Jan D., Neil A. Segal, Angelo Cacchio, John P. Furia, Antonio Morral, and Nicola Maffulli. “Home training, local corticosteroid injection, or radial shock wave therapy for greater trochanter pain syndrome.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine 37, no. 10 (2009): 1981-1990

Ruta, Santiago, et al. “Ultrasound evaluation of the greater trochanter pain syndrome: bursitis or tendinopathy?.” JCR: Journal of Clinical Rheumatology21.2 (2015): 99-101.

Michaud, Thomas C. Human locomotion: the conservative management of gait-related disorders. Newton Biomechanics, 2011.

Del Buono, Angelo, et al. “Management of the greater trochanteric pain syndrome: a systematic review.” British medical bulletin 102.1 (2012): 115.

Williams, Bryan S., and Steven P. Cohen. “Greater trochanteric pain syndrome: a review of anatomy, diagnosis and treatment.” Anesthesia & Analgesia 108.5 (2009): 1662-1670.